Representing Loops: An Exploration of Non-Sequential Logic Execution

Most programming languages that target DTR have some sort of looping behavior. As an example, consider the logic to calculate the sum of the first 10 integers, written in Rust.

let num = 0;

for i in 1..10 {

num += i

}

println!("Sum of 1 through 10 is: {}", num);

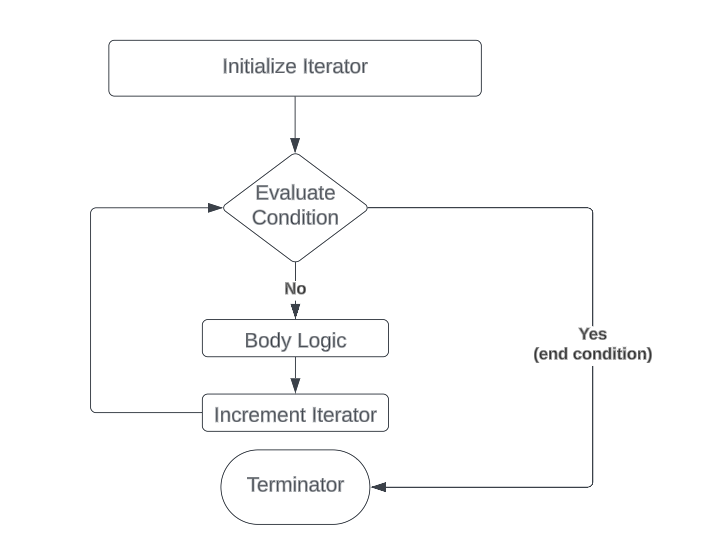

Constructing a DTR representation is challenging; this logic is not sequentially executed, requiring repetitive calls to some body of code until a condition is met. Visually, we do something like this:

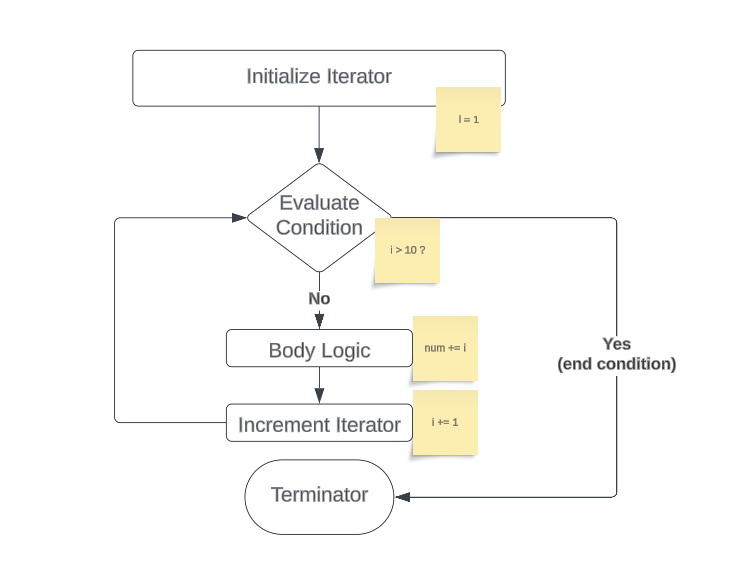

We can then use yellow sticky notes to “fill in” each box with the relevant code from the example.

With an idea of how we might visually represent the looping Rust code, can we come up with a way to represent this with DTR? Unfortunately, while we do have a way to represent a fork in execution via scoping:

// [0] CONDITIONAL_JUMP_0 = i <= 10

{ instruction: "evaluate", input: (less_than_or_equal_to, i, 10), assign: CONDITIONAL_JUMP_0, scope: 0 }

// [0] if CONDITIONAL_JUMP_0, scope = 1

{ instruction: "jump", input: (CONDITIONAL_JUMP_0, 1), scope: 0 }

// [1] num = num + i

{ instruction: "add", input: (num, i), assign: num, scope: 1 }

// [1] i = i + 1

{ instruction: "add", input: (i, 1), assign: i, scope: 1 }

the simplistic (naive?) sequential model we have initially adopted does not have a clean way of representing “go back to some previous point in execution”.

For this, we will introduce:

- instruction ids

- a

gotoinstruction

»»»[side bar]»»»

A Note on Goto: most modern programming languages do not support goto statements. Many (like this blog post) will point out the costly complexity of goto statements as a primary driver for their avoidance. While introducing the notion of a goto might make some folks uncomfortable, we do so sparingly and with the intention of eventual removal (especially if we see folks abusing it). For now, however, the goto will simply live “in the backend” (as an artifact of translation between Rust and DTR). We plan to re-evaluate this decision once Digicus evolves from a visualization first tool to a creation native tool.

«««[side bar fin]«««

In summary, a loop has three main parts:

- initialize iterator

- evaluate condition

- if continuing execute body, then increment iterator

Notice that (1) can be completed outside the actual loop evaluation. Furthermore, the “if continuing” flow can leverage the scoping behavior as already defined for conditionals following the sequential instruction flow.

Thus, with what we defined above, we are almost there. Let’s now take what we had, add id’s, then add a sixth goto instruction which exists in scope 1 and goes back to instruction 1:

{ id: 0, instruction: "assign", input: (1), assign: i, scope: 0 }

########### Loop ###########

// [0] CONDITIONAL_JUMP_0 = i <= 10

{ id: 1, instruction: "evaluate", input: (less_than_or_equal_to, i, 10), assign: CONDITIONAL_JUMP_0, scope: 0 }

// [0] if CONDITIONAL_JUMP_0, scope = 1

{ id: 2, instruction: "jump", input: (CONDITIONAL_JUMP_0, 1), scope: 0 }

// [1] num = num + i

{ id: 3, instruction: "add", input: (num, i), assign: num, scope: 1 }

// [1] i = i + 1

{ id: 4, instruction: "add", input: (i, 1), assign: i, scope: 1 }

// [1] go back to conditional (instruction id = 1)

{ id: 5, instruction: "goto", input: (1), scope: 1 }

############################

With this, we’ve got a viable representation of loops. However, before claiming victory, let’s see if we can easily translate back to rust.

Converting this back to Rust

With each instruction having an id above, we can associate the instructions to the generated Rust.

// [0]

let mut i = 1;

// [1] & [2]

while i <= 10 { // <------------

// [3] // |

num = num + i; // |

// [4] // |

i = i + 1; // |

// [5] ----------------------|

}

Note: while we did translate back to a while instead of a for loop, these are functionally the same.

A Final Test: Nested Loops

This time, let’s try a nested loop (in this simplified example, we will ignore each block’s body).

for i in 1..10 {

for j in 0..5 {}

}

Now for the DTR.

// [0] i = 1

{ id: 0, instruction: "assign", input: (1), assign: i, scope: 0 }

########### Loop ###########

// [0] CONDITIONAL_JUMP_0 = i <= 10

{ id: 1, instruction: "evaluate", input: (less_than_or_equal_to, i, 10), assign: CONDITIONAL_JUMP_0, scope: 0 }

// [0] if CONDITIONAL_JUMP_0, scope = 1

{ id: 2, instruction: "jump", input: (CONDITIONAL_JUMP_0, 1), scope: 0 }

// [1] j = 0

{ id: 3, instruction: "assign", input: (0), assign: j, scope: 1 }

// [1] CONDITIONAL_JUMP_1 = j <= 5

{ id: 4, instruction: "evaluate", input: (less_than_or_equal_to, j, 10), assign: CONDITIONAL_JUMP_1, scope: 1 }

// [1] if CONDITIONAL_JUMP_1, scope = 2

{ id: 5, instruction: "jump", input: (CONDITIONAL_JUMP_1, 2), scope: 1 }

// [2] j = j + 1

{ id: 6, instruction: "add", input: (j, 1), assign: j, scope: 2 }

// [2] go back to conditional (instruction id = 4)

{ id: 7, instruction: "goto", input: (33333), scope: 2 }

// [1] i = i + 1

{ id: 8, instruction: "add", input: (i, 1), assign: i, scope: 1 }

// [1] go back to conditional (instruction id = 1)

{ id: 9, instruction: "goto", input: (1), scope: 1 }

############################

And finally back to Rust.

// [0]

let mut i = 1;

// [1] & [2]

while i <= 10 { // <------------

// [3] |

let j = 0; // |

// [4] & [5] |

while i <= 5 { // <--- |

// [6] // | |

j = j + 1; // | |

// [7]------------| |

} // |

// [8] // |

i = i + 1; // |

// [9]----------------------|

}