Digicus

Scratch for Smart Contracts

me[at]robdurst[dot]com

With it’s launch in 2015, Ethereum 1 brought smart contracts to the forefront of the blockchain ecosystem. These smart contracts were based on the (original?) definition laid out by Nick Szabo in 1996 2: “[a] smart contract is a set of promises, specified in digital form, including protocols within which the parties perform on these promises.”

As implemented today, smart contracts are typically turing complete and rely on a VM coupled with the underlying blockchain nodes. Like any typical VM, a “smart contract handling VM” handles some set of instructions, typically byte code, charging fees for execution, storage, etc. Contracts may be written in a “blockchain native” language like Solidity 3 or a pre-existing language that is compiled to a format the VM supports (i.e. Rust compiled to WASM which may run on Stellar’s Soroban 4). While these smart contract development ecosystems have matured greatly over the past few years, writing a non-trivial, secure, correct smart contract is not easy (Google smart contract hack and you’ll see a plethora of examples). Today, various tools exist to solve this problem. Grouped generally, there are a few approaches:

- Allow folks to use the programming language they are most familiar with (Hyperledger Fabric 5)

- Give folks the best developer experience possible

- Provide a set of re-usable, well vetted, well tested, and well understood boiler-plate, templated smart contracts (OpenZepplin 6)

We propose a fourth approach: making the smart contract language itself more approachable. Fundamentally, the barriers to entry are overwhelmingly numerous. For example, in order to be a competent smart contract developer on the Stellar’s Soroban, you need to be familiar with how blockchains work, have a strong foundation in smart contracts, and be functional in the Rust programming language. Expecting non-technical participation and a painless onboarding experience for newcomer developers is not realistic. We believe a blockchain agnostic, visual, block-based programming environment will facilitate a more accessible onboarding experience for all. Specifically, we’ve built Digicus, an intuitive, simple, Lego-like IDE, backed by Digit, a compiler plugin framework for seamless transpilation between existing smart contract languages (i.e. Solidity) and frameworks (i.e Stellar’s Soroban Rust SDK) and our intermediate representation (DTR: Digicus Textual Representation). Digicus is the blockchain ecosystem’s Scratch 7, a smart contract 101 platform that will help onboard newcomers into our world, aiding their journey to “smart contract 201” and beyond.

Table of Contents

- Table of Contents

- Existing Work and Inspiration

- Solution

- An Overview

- The Digicus IDE

- A Compiler Plugin Framework

- Digicus Textual Representation

- Supported Instructions

- Instruction Execution Flow

- Valid Types - Conclusion

- Latest Status - Grant Acknowledgements

- References

Existing Work and Inspiration

The idea of a platform like Digicus is not a completely novel idea.

A 2021 paper titled SmartBuilder: A Block-based Visual Programming Framework for Smart Contract Development states 8:

In this paper, we introduce SmartBuilder, a block-based visual programming framework for building smart contracts using extended Google Blockly libraries. It allows Hyperledger Fabric smart contract (also known as Chaincode) development learners or non-expert users to build smart contracts using visual blocks without writing a single code

This solution claims to have developed a commercial application of their proposed framework for the Aergo blockchain 9.

A second paper, Scilla: a Smart Contract Intermediate-Level LAnguage focuses on the idea of a smart contract intermediate language 10:

This paper outlines key design principles of Scilla—an intermediate-level language for verified smart contracts. Scilla provides a clean separation between the communication aspect of smart contracts on a blockchain, allowing for the rich interaction patterns, and a programming component, which enjoys principled semantics and is amenable to formal verification. Scilla is not meant to be a high-level programming language, and we are going to use it as a translation target for high-level languages, such as Solidity, for performing program analysis and verification, before further compilation to an executable bytecode. We describe the automata-based model of Scilla, present its programming component and show how contract definitions in terms of automata streamline the process of mechanised verification of their safety and temporal properties

This paper focuses on verification, not ease of development (however, a very interesting idea Digicus might be able to adopt later).

Furthermore, the idea of a compiler framework is heavily influenced by LLVM 11.

LLVM defines a common, low-level code representation in Static Single Assignment (SSA) form, with several novel features: a simple, language-independent type-system that exposes the primitives commonly used to implement high-level language features; an instruction for typed address arithmetic; and a simple mechanism that can be used to implement the exception handling features of high-level languages (and setjmp/longjmp in C) uniformly and efficiently. The LLVM compiler framework and code representation together provide a combination of key capabilities that are important for practical, lifelong analysis and transformation of programs.

The beauty of LLVM as a general target for high level languages allows language developers to get (a) a bunch of optimizations and (b) a whole host of backends for free. Its importance to the compiler ecosystem cannot be understated.

Digicus is a novel combination of these ideas, designed practically with the intention of developing a production application.

Solution

An Overview

Our solution requires three distinct pieces of technology:

- an IDE (a visual programming language)

- a compiler plugin framework

- a well-defined intermediate representation language

The IDE is where a user will spend most of their time viewing and modifying smart contracts. The IDE is integrated with Digit, our compiler plugin framework which is responsible for transpiling between source language(s), DTR, and target language(s). Within Digit resides an implementation of dtr_core, a Ruby gem that adheres to the DTR specification. While dtr_core is effectively the reference implementation, based on our appreciation of Rob Pike 12 and his acknowledgement of the importance of the Go spec 13, please consider the specification of DTR to be the source of truth and dtr_core to be just an implementation.

Visual Programming Language

The smart contract developer tooling community has yet to find PMF for a tool to aid novice developers in the creation of secure and performant smart contracts. While we don’t naively believe this is due to a lack of effort, we instead attribute it to implementations focused on the wrong level of abstraction.

Today, there are more-or-less three levels of abstraction:

- high level programming languages (i.e. Solidity)

- visual programming languages that syntactically mirror source code

- well-vetted template libraries (i.e. OpenZepplin)

Thus far, Digicus (and many of the earlier VPL attempts in this space) have been focused on (2). While not yet fully formed, designed, or even really described in this specification document, we believe there is a 2.5. In such a world, we will design an abstraction over high level source code which eliminates known security violations and/or performance degradations, guiding the novice developer towards a happy path solution (we call this a “shift left” solution” as we’re shifting the addressing of security and performance closer to the beginning of the SDLC).

[August 2024] We don’t yet know what this looks like. We’re engaging in conversations across our network in pursuit of a solution… stay tuned!

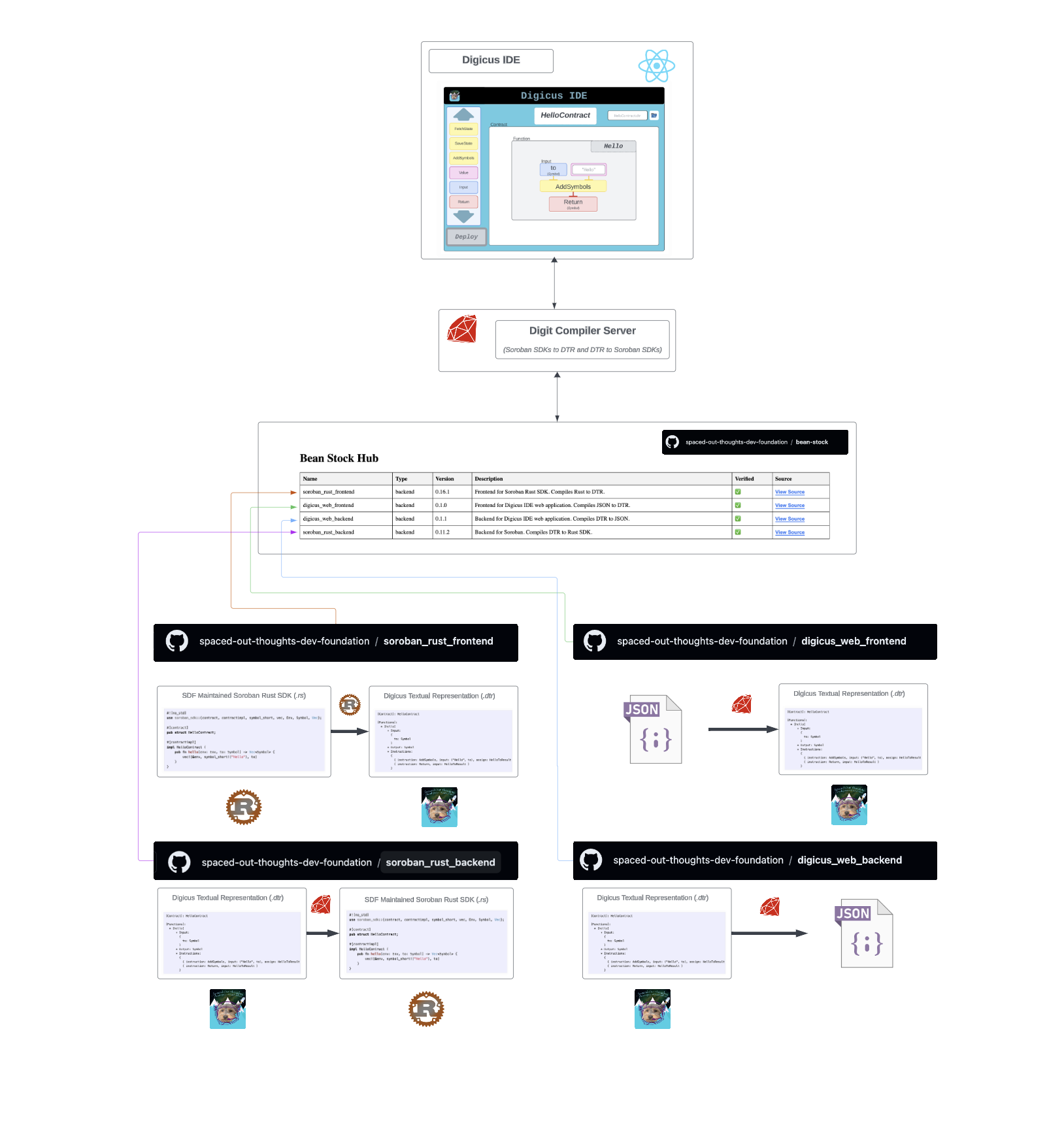

Architecture:

Our compiler plugin framework is leveraged by Digit via the Bean Stock Compiler Plugin (pod) Hub 14. Bean Stock sources pods via git submodules, where each submodule has a bean_stock_manifest.yaml file describing the pod. Here is an example:

name: soroban_rust_frontend

type: backend

version: 0.16.1

description: Frontend for Soroban Rust SDK. Compiles Rust to DTR.

command: make run FILEPATH

author: rob | me@robdurst.com

source: https://github.com/spaced-out-thoughts-dev-foundation/soroban_rust_frontend

The Digit server’s Dockerfile can then fetch and compile/setup each submodule upon docker build based on the manifest. Wthi this in place, Digit will be able to handle various transpilations at runtime as requested by Digicus.

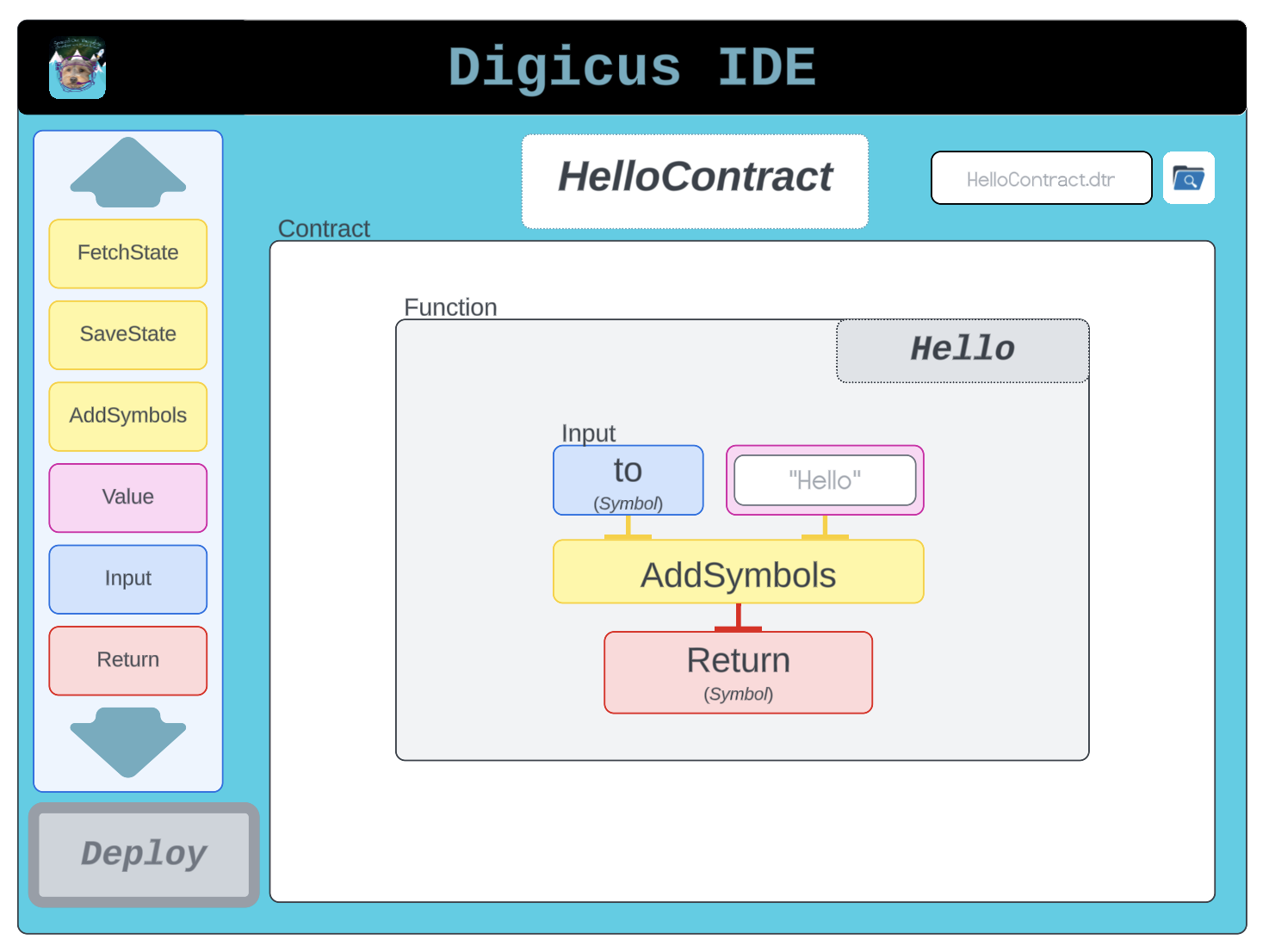

The Digicus IDE

Below is an initial mockup of the MVP user interface.

When developing with Digicus, users will be able to name the contract, drag and drop block components into the interactive function creator, and then they will be able to perform minimal, chain agnostic testing of the contract. The UI/UX for this will be based heavily off of the well-tested, mature Scratch programming platform. Furthermore, a plethora of features will be supported to make this a first class smart contract development interface, including but not limited to:

- common vulnerability detection

- autocomplete (eventually some sort of Copilot-esque flavor as well 15)

- realtime syntax/semantic error recognition with sensible warnings and recommendations for improvement

- chain specific integration testing

The IDE will support two workflows: (1) upload and modify and (2) net new creation.

Workflow #1: Upload and Modify: users will be able to upload a smart contract from one of the supported smart contract programming languages/frameworks. Once uploaded, users can modify as they wish.

Workflow #2: Net New Creation: users will be able to create a generic smart contract from scratch. However, they will not always need to start from scratch; a library of common templates will be available for bootstrapping.

While a full IDE is the goal of this work, we anticipate the visualization feature to be immediately useful with the possibility to embed within existing smart contract analysis/explorer/etc. software today.

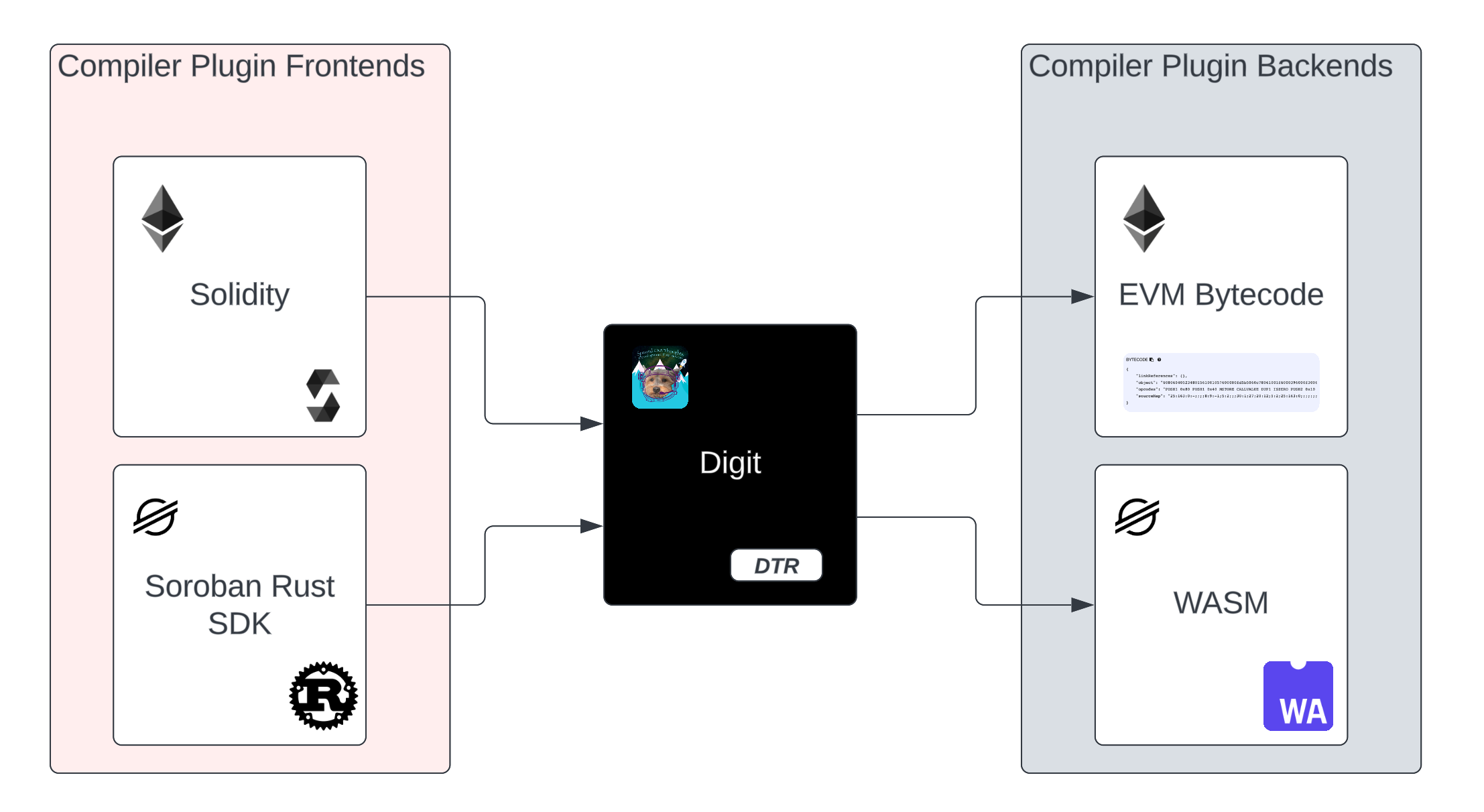

A Compiler Plugin Framework

Digit, Digicus’s compiler plugin framework, enables the ambitious software developer to add support for their blockchain smart contract programming language (or framework) of choice. To do so requires the development of a bidirectional transpiler, from source to DTR and DTR to source. We aid this development by way of example plugins and a central repository for hosting these such that they are discoverable and auto-magically integratable with the IDE.

A plugin is an executable binary with two methods:

to_dtr(source_language: String) --> String

from_dtr(dtr: String) --> String

The Spaced Out Thoughts Development Foundation aims to initially support:

- Stellar’s Soroban Rust SDK

We’re biased, we love Stellar and given the novelty of their solution to global cross border payments, a strong technical foundation, and the very recent launch of Soroban, focusing here was a no brainer.

However, given the flexibility of the compiler plugin designed, one day, Digit will be able to support the following:

Digit enables the seamless translation of contracts not only from source to DTR, but from source A to Target B. There are numerous ecosystem examples of targeted transpilation libraries 16 and even blockchain interoperability17. Digicus aims to go one step further, the generalization of smart contracts as whole. We believe this is layer 3 at its finest!

Digicus Textual Representation

DTR is defined by ASCII text files with the .dtr ending. Each file contains the definition for a single contract and consists of five sections:

- Contract: where the name of the contract is specified

- State: where we define the type and initial data for each variable

- UDTS: where we define user defined types

- Interface: where we define each externally visible method (name, input, output, body)

- Helpers: where we define each internal method (name, input, output, body)

- Non-translatables: some source languages are more expressive than the target language. Thus, in an effort to allow easier transpilation back, we’ve included an optional section to store relevant metadata unique to the source.

If a section is omitted, it will be assumed to be non-existent.

Overall structure:

[Contract]: CONTRACT_NAME

[State]:

* STATE_DEFINITION

...

* STATE_DEFINITION

:[State]

[UDTs]:

* UDT_DEFINITION

...

* UDT_DEFINITION

:[UDTs]

[Interface]:

* FUNCTION_DEFINITION

...

* FUNCTION_DEFINITION

:[Interface]

[Helpers]:

* FUNCTION_DEFINITION

...

* FUNCTION_DEFINITION

:[Helpers]

[NonTranslatable]:

TEXT_IN_ANY_FORMAT

:[NonTranslatable]

STATE_DEFINITION:

[STATE_NAME]:

* Type: TYPE_NAME

* Initial Value: VALUE

Where TYPE_NAME can be any valid type. (TBD) do we want a 1-to-1 mapping of Rust types to .dtr types? Yes for MVP, but maybe as we implement this it will be (a) easier to generalize and/or (b) clear that new users need not care about this and so we can make smart decisions for them. Eventually we may rethink this when we expand to other frontend targets.

UDT_DEFINITION:

All user defined types are objects. An object is a named entity with zero or more typed fields.

[Foo]:

* Bar: Integer

* Baz: String

Enums are fairly typical. Consider how we might represent the two flavors of Rust enums as objects.

Typical enum:

// Rust

enum TrafficLight {

Red,

Green,

Yellow,

}

...

// Digicus

// UDT

[TrafficLight]

* Kind: Integer

// Function

[TrafficLightValue]

* Input

{

traffic_light: TrafficLight

}

* Output: Boolean

* Instructions

$

{ instruction: conditional_jump, input: (greater_than, traffic_light.Kind, 3, 1), scope: 1 }

{ instruction: return, input: (False), scope: 1 }

{ instruction: return, input: (True), scope: 1 }

$

...

Enum variant:

// Rust

enum Shape {

Circle(f64),

Rectangle(f64, f64),

}

...

// Digicus

[Shape]

* Circle: Tuple<Float>

* Rectangle: Tuple<Float, Float>

FUNCTION_DEFINITION:

[FUNCTION_NAME]:

* Input:

{

INPUT_NAME: TYPE_NAME,

...

INPUT_NAME: TYPE_NAME

}

* Output: TYPE_NAME

* Instructions:

$

{ id: UUID, instruction: INSTRUCTION_NAME, input: (VALUE_NAME: VALUE,..., VALUE_NAME: VALUE), assign: ASSIGN_NAME, scope: SCOPE_LEVEL },

...

{ id: UUID, instruction: INSTRUCTION_NAME, input: (VALUE_NAME: VALUE,..., VALUE_NAME: VALUE), assign: ASSIGN_NAME, scope: SCOPE_LEVEL }

$

Note:

- the input section is optional

- the output section is optional

- output may be at most one value

- an instruction need not have an input nor an output

- an

ASSIGN_NAMEis a local variable which may be referenced by following instructions INSTRUCTION_NAMEis the name of a subset of supported rust expressions see supported instructionsSCOPE_LEVELis an unsigned integer detailing which level of accessibility an instruction is executed within. It is required

Supported Instructions

Defining a set of common instructions across all blockchains is challenging. Thus, it is likely this list will be in flux;until otherwise stated, this list may be incomplete.

| Operation Name | Inputs | Assign | Category | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| assign | 1 | Required | Basic | given some input value, assign to ASSIGN_NAME |

| evaluate | >1 | Optional | Basic | given a method name and 0 or more inputs, execute method. At this time, evaluate is a fairly loose catch-all for not explicitly defined operations |

| 1 | None | Basic | given some value, print it to standard out | |

| exit_with_message | 1 | None | Terminating | immediately end execution, returning message |

| return | 1 | None | Terminating | return from function with input value |

| and | 2 | Required | Logical | assign to ASSIGN_NAME result of “and-ing” two values |

| or | 2 | Required | Logical | assign to ASSIGN_NAME result of “or-ing” two values |

| goto | 1+ | None | Control Flow | conditional if two inputs. In this case, first input is the condition to evaluate. If that is true, or there is only one input, move in code to the first input (an instruction id) |

| jump | 1+ | None | Control Flow | conditional if two inputs. In this case, first input is the condition to evaluate. If that is true, or there is only one input, jump to scope level |

| end_of_iteration_check | 1 | Required | Control Flow | check on input to see if at end of iteration. Return result to ASSIGN_NAME |

| field | 2 | Optional | Object | access a field on an object and assign result to ASSIGN_NAME |

| instantiate_object | 1+ | Optional | Object | initialize an object by first passing in the type of object and the passing in each initial values for its fields. Supported types here include: Dictionary, List, Range, Tuple, and UDT. For UDTs, the second input is the name of the UDT. |

| add | 2 | Required | Binary | assign to ASSIGN_NAME result of adding two value |

| subtract | 2 | Required | Binary | assign to ASSIGN_NAME result of subtracting two value |

| multiply | 2 | Required | Binary | assign to ASSIGN_NAME result of multiplying two value |

| divide | 2 | Required | Binary | assign to ASSIGN_NAME result of dividing two value |

| try_assign | 2 | Required | Basic | assign to ASSIGN_NAME the result of the attempted assign of input index 0 to input index 1 |

| increment | 1 | None | Unary | An operation to increment the input (however that may be implemented) |

| unary | 2 | Optional | Unary | Basic unary operations like ! and - |

| break | 0 | None | Control Flow | Breaks out of the current execution flow. |

Instruction Execution Flow

Instruction flow is determined by two main factors:

- the top to bottom position of the instruction within the collection

- the scope of the instruction

Much like traditional computing, instructions here, are executed in the order defined, from top to bottom. However, the instruction pointer 18 is scope-aware; thus, if the current scope is 7, but the instruction pointed at is a scope of anything besides 7, the instruction pointer will transition to the next instruction in the collection. Scopes help us isolate functional blocks of logic and as we move through the execution of a program, we simulate a stack frame based on these scopes.

To illustrate, consider the representation of an if-else block in DTR:

// ====== scope 0 ======

// CONDITONAL_RESULT_1 = x > 10

{ instruction: evaluate, input: (greater_than, x, 10), assign: CONDITONAL_RESULT_1, scope: 0 }

// if CONDITONAL_RESULT_1, scope => 2

{ instruction: jump, input: (CONDITONAL_RESULT_1, 2), scope: 0 }

// else, scope => 3

{ instruction: jump, input: (3), scope: 0 }

// ====== scope 2 ======

// print("we are in scope 2")

{ instruction: print, input: ("we are in scope 2"), scope: 2 }

// scope => 0

{ instruction: jump, input(0), scope: 2}

// ====== scope 3 ======

// print("we are in scope 3")

{ instruction: print, input: ("we are in scope 3"), scope: 3 }

// scope => 0

{ instruction: jump, input(0), scope: 3}

// ====== scope 0 ======

{ instruction: print, input: ("we are back in scope 0"), scope: 2 }

We start by evaluating x > 10. If it is true, we navigate to scope 2, print “we are in scope 2”, then navigate back to scope 0 where we print “we are in scope 0”. If x is less than or equal to 10, then we navigate to scope 3, print “we are in scope 3”, finally navigating back to scope 0 where we print “we are in scope 0”.

Equivalent ruby code would look like this:

if x > 10

print "we are in scope 2"

else

print "we are in scope 3"

end

print "we are in scope 0"

Going “backwards” to repeat ourselves

There are times where it might be useful to repeat some logic. In most programming languages, you can accomplish this with a loop:

println!("Before loop")

for i in 0..42 {

println!("Iteration: {}", i);

}

println!("After loop");

With only the basic scope-based sequential execution we’ve laid out thus far, the only way to replicate the above looping logic is by loop unrolling 19. However, that is not practical. Thus, we’ve introduced the concept of an instruction id and a goto instruction type. The goto instruction (as outline in the table of the preceding section) accepts a single input, the instruction id to navigate to. Thus, we can replicate the above code with the following collection of DTR instructions.

{ id: 0, instruction: "print", input: ("Before loop"), scope: 0 }

{ id: 1, instruction: assign, input: (0), assign: i, scope: 0 }

{ id: 2, instruction: evaluate, input: (less than, i, 42), assign: LOOP_CHECK, scope: 0 }

{ id: 3, instruction: jump, input: (LOOP_CHECK, 1), scope: 0 }

{ id: 4, instruction: "print", input: ("Iteration: {}", i), scope: 1 }

{ id: 5, instruction: "increment", input: (i), scope: 1}

{ id: 6, instruction: "goto", input: (3), scope: 1}

{ id: 7, instruction: "print", input: ("After loop", scope: 0) }

Here we assign 0 to i. Then we check if i is less than 42. If so, we navigate to scope 1. In scope 1, we print our message, increment i, then navigate back to the loop check. This code will continue executing until we fail the loop check. Once we fail, we don’t jump to scope 1 and so instructions with the ids of 4, 5, and 6 are skipped. Thus, we print “After loop” and the program terminates.

At this point, we’ve outlined the basics of instruction execution flow for DTR.

Valid Types

Basic Types

A.K.A. primitive types.

Digicus supports the following:

- Address

- BigInteger

- Boolean

- Float

- Integer

- String

Container Types

Types that contain types.

Digicus supports the following:

- List: homogenous, single unary (ex.

List<Integer>) - Dictionary: homogenous in dimension, binary arity (ex.

Dictionary<String, Integer>) - Range: an iterator over some values (ex.

Range<Integer>) - Tuple: n-ary arity (ex.

Tuple<Integer, Integer, String>)

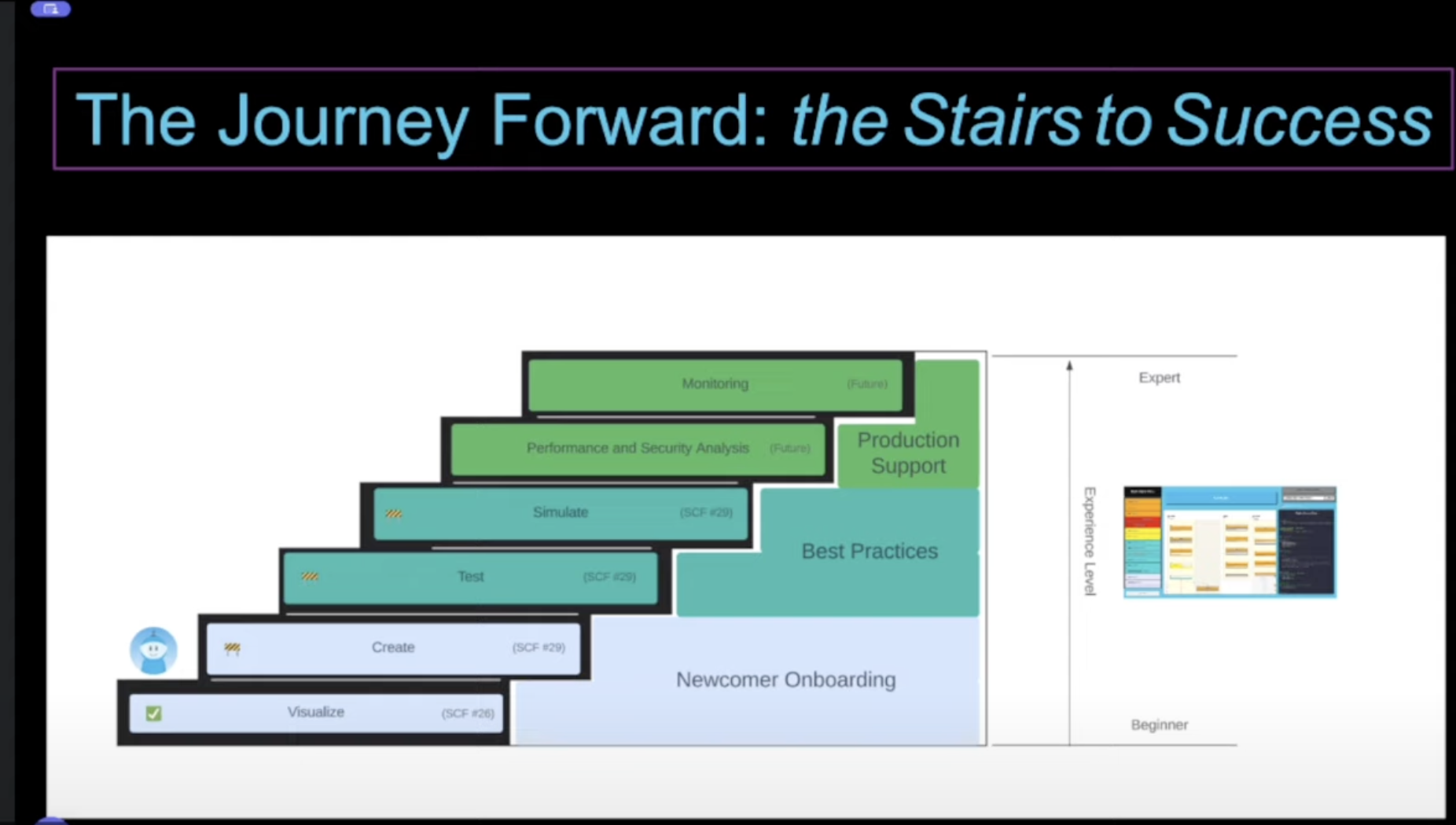

Conclusion

We believe Digicus will revolutionize the way budding smart contract newcomers onboard into this powerful and wonderful ecosystem. Furthermore, as with scratch we expect folks to eventually graduate from Digicus native smart contracts to leveraging the core programming language of their blockchain of choice. At this point, Digicus will become a sidecar IDE; opened in a window adjacent to their text editor, smart contract developers will be able to leverage the incredible tooling of Digicus to enhance their current development flow.

Presented visually, we believe the evolution of Digicus will look like this:

As time goes on, we will work with developers to solicit feedback and conduct surveys in order to ensure we have the greatest possible positive impact on this community. These survey results will be posted on our website.

Until then, please feel free to follow our coding journey here and experiment with the IDE here.

Latest Status

At time of writing (August 2024) we have accomplished our SCF #26 Activation Award deliverables (demo’d here) and just recently pitched during the SCF #29 Community Award demos; we at Spaced Out Thoughts are huge fans and supporters of Stellar and thus seek to leverage our past experience with SDF to work within the ecosystem we know best.

Grant Acknowledgements

We’re forever grateful for support via the following ecosystem grants:

- Stellar Community Fund SCF #26 Activation Award

- Stellar Community Fund SCF #29 Community Award

Furthermore, as this work is ambitious and ongoing, we’re actively seeking additional funding opportunities.

References

-

Ethereum: A Next-Generation Smart Contract and Decentralized Application Platform. By Vitalik Buterin (2014) ↩

-

Smart Contracts: Building Blocks for Digital Markets - Nick Szabo 1996 (partial rewrite of original) ↩

-

Solidity: A statically-typed curly-braces programming language designed for developing smart contracts that run on Ethereum ↩

-

OpenZepplin: Securely Code, Deploy and Operate your Smart Contracts ↩

-

SmartBuilder: A Block-based Visual Programming Framework for Smart Contract Development: Mpyana Mwamba Merlec; Youn Kyu Lee; Hoh Peter In ↩

-

Scilla: a Smart Contract Intermediate-Level LAnguage: Ilya Sergey, Amrit Kumar, Aquinas Hobor ↩

-

LLVM: A Compilation Framework for Lifelong Program Analysis & Transformation: Chris Lattner, Vikram Adve ↩

-

Rob Pike - What We Got Right, What We Got Wrong, GopherConAU 2023 ↩